“What the FARC?”

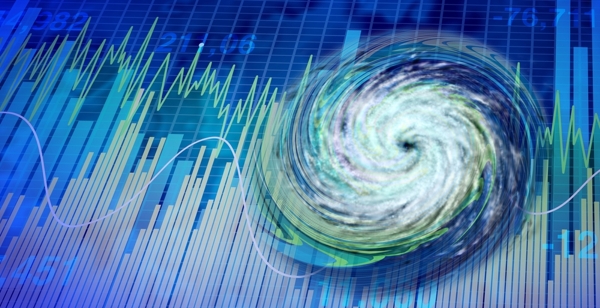

Doug Casey’s Note: What you’re about to read is something that makes me envious. My friend Kolja invited me on this expedition, but I got caught up in things that were urgent and dropped the ball on something important.

I rationalized missing the adventure because I’d been to the boonies in Colombia a half-dozen times over the years, when FARC was still quite active, and had my picture taken while I was holding an FAL surrounded by cammy-clad soldiers, but this is way better.

Kolja’s article is what we call a “long read” in today’s ADD world. It will probably take you 10 minutes or so. But how could it be shorter and still give you a flavor of a trek to a rebel republic in the middle of nowhere and of people like the Communist Lara Croft and a warrior who personally took out perhaps 800 of the enemy?

Let us know what you think…

My diary of the first foreign tourist trip to the former rebel Republic of Marquetalia, Colombia

By Kolja Spori

Had someone told me a while ago that I would meet all the leaders of FARC, the Latin American guerrilla fighters, in their hidden founding place deep in the Colombian jungle, I would have thought I had been caught in a daydream. Or perhaps it’s a nightmare, because over the last half-century, the FARC have gained worldwide notoriety for their never-ending kidnappings of civilians, their extortion of businessmen, and their endorsement of Marxism-Leninism. The latter constituted the biggest crime, in my book, as I am a thoroughbred Austrian School libertarian.

Here is a quick overview of the situation in Colombia. During the years of “La Violencia,” following the murder of left-wing presidential candidate Jose Gaitan in 1948, armed opposition groups hid in the remote highland jungles, founding no less than eight quasi-independent republics south-west of Bogota with their resistance center known as the “Republic of Marquetalia.”

When the government raided the lonely mountain hut of rebel leader Manuel Marulanda in 1964 during the epic Battle of Marquetalia, 48 guerrillas managed to miraculously escape the 1,600 government troops and even shot down 2 government helicopters. This founding myth created the communist “Bloque Sur,” the precursor of FARC, that swelled from those 48 fighters to more than 20,000 members in the end.

In 1966, Manuel Marulanda officially founded FARC, the “Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarios de Colombia,” together with his comrade Jacobo Arenas, who later published the influential “Marquetalia Diaries.” Their main objective was to free the indigenous people from the foreign imperialists and to fight the notorious unequal distribution of agricultural land, ever since European conquistadores like Columbus, Ehinger, Belalcazar, and Balboa grabbed control of the continent half a millennium ago.

Fast forward. After 50 years of fighting for their “good cause” without any tangible results, FARC signed the Havanna ceasefire agreement with the Colombian government in June 2016, signed a revised peace agreement (after a failed referendum against them) in November 2016, laid down their arms to the United Nations by June 2017, and have officially been a legal political party called “Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Comun” since September 2017, with 5 seats guaranteed in the House of Representatives and 5 seats guaranteed in the Senate.

Over those 50 years, according to Wikipedia, the Colombian civil war caused about 220.000 casualties, three-quarters civilians, and more than 5 million internal refugees! Official UN statistics attribute the vast majority of the killings, 80%, to right-wing paramilitaries, 8% to official government forces, and 12% to left-wing fighters, here mainly FARC (plus ELN and M19).

My local contacts tell me that the UN numbers are heavily skewed in favor of FARC, and it presents them as lame ducks. However, the paramilitaries only came into the picture after 1984, while FARC was already killing 20 years prior to that.

At the moment, despite the formal peace, there remain renegades on both sides: about 10 to 20% of former FARC members chose to continue their armed fight, mainly led from Venezuela.

On the other hand, the paramilitaries and the government have been accused by FARC of killing almost 200 peaceful FARC members clandestinely (some may have been victims of FARC dissidents or standard crimes). An intelligent question to ask is why there have been no faces, heroes, diaries, or history books ever published about the right-wing paramilitaries in the Western media.

One of the answers is that the Colombian conflict is a triangulated conflict that is orchestrated by outsiders with geopolitical interests way above the Colombians’ heads. During the Cold War, the government and paramilitaries were openly supported by the US, and the FARC was visibly sponsored by the Soviet Union.

To date, the internal conflict is still kept alive because the reasons for popular discontent remain: cocaine money has replaced secret American or Soviet funding, and the paramilitaries don’t have to reveal their faces or disarm themselves (some are simple drug dealers, while others are influential farmers).

The left and right are usually agitated all over the world in a Hegelian dialectic fashion, or “strategy of tension.” In the case of Colombia, the geostrategic reason behind the artificial tension is the Panama Canal. This neuralgic choking point for world trade and naval military transport has to be safeguarded at any cost, by the powers-to-be. The cost of human life in their constructed conflicts is obviously considered cheap.

The US even built their School of the Americas for the training of conflict parties, paramilitaries, subversives, interrogators, drug barons, and so on, right on the Panama Canal. The former house of horrors nowadays hosts the recommendable Melia Hotel Colon. The same techniques continue to be taught at the so-called Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation in Fort Benning, Columbus, Georgia.

Few scholars will remember that the Panama Canal project was taken over by the US in a questionable deal with the corrupt Frenchman Philippe Bunau-Varilla around the turn of last century. Panama was then separated from Colombia in a covert operation by the US prior to World War I, similar to the current US-sponsored regime changes in South Sudan, Kosovo or Ukraine. Of course, they were taking advantage of the 1000-day war being fought between Colombian liberals and conservatives from 1898 to 1901.

After the illegal cessation and occupation of Panama was officially acknowledged by the US in the Carter-Torrijos Treaty in 1977, it became necessary to quasi-annex the small country once again through the US invasion in 1989, leaving Panama without an army of its own. And, of course, leaving control of the Panama Canal to the US.

To ensure that no one attacks the Canal from the South, all access has been blocked by the US, not only through apparently dangerous “guerrilla groups” or “drug cartels,” but also by “forces of nature,” allowing the previous road path connection between Panama and Colombia to be grown over by jungle, in the so-called “Darien Gap,” the missing link of 70 kilometers, within the 22.500 kilometers of the “Panamericana Highway,” which otherwise leads all the way north-south across the continent, from Dead Horse in Alaska to Ushuaia in Patagonia.

These missing 70 kilometers of asphalt are a pain for trans-continental overlanders who have to forward their vehicles or freight by container ship or by cargo plane, which costs a lot more money than building a road. Don’t ask yourself, “Who builds the roads?” It is usually a private economic initiative; rather, ask yourself, “Who blocks the roads?” It is usually state actors, sometimes hiding behind false flags. (Why the US clandestinely leads the current refugee trek, more than 60.000 on foot through the Darien Gap since 2012, is a topic for another day.)

My trip to Colombia, on the “Peace Road to Marquetalia,” under the supervision of the United Nations, together with FARC, police, military, and other Colombian government agencies, was a proverbial “road” built entirely by private initiative—and yet we operated not-for-profit. That must be hard to understand for friends of statism or other forms of non-voluntaryism.

Before I sound like a virtue signaller, here is the background. I have been organizing the annual get-together of the world’s most traveled people, the ETIC, Extreme Traveler International Congress, for about 10 years, pro bono, and always in hard-to-get-to locations. Most of us have been to all of the 193 UN member countries in the world. One of our extreme travelers, Jack Goldstein, owner of the Lancaster House Hotel in Bogota, came up with the idea to host one such congress in his home country of Colombia, in one of the completely off-limit FARC areas.

Through an old business acquaintance who now works for the UN Verification Mission in Colombia, Jack got the trust of the United Nations, who then decided to introduce him to the FARC operative who was responsible for laying down their arms to the UN, a former fighter known as Rubin Morro, now the Director of Communications for the political party FARC, author and poet, using his real name, Martin Cruz Vega.

Jack and Martin slowly but surely got the support of other FARC leaders for a foreign tourist group to become the first visitors to Marquetalia. This demonstrated to the outside world that the new FARC is now committed to peace and is capable of conducting a major commercial operation, building a permanent road to peace, which will also generate tourism money in the future for small traders, mule herders, tent builders, cooks, and other helpers in the remote rural area, but in particular to shine a bright road sign for Colombia’s future.

Once the UN and FARC had endorsed the undertaking, the local communities and the ministry of tourism also came along. Finally, both the military and the police had to cooperate officially, and they did so in a surprisingly efficient, friendly, and non-obstructive way. In the end, even the Presidential Palace called Jack Goldstein to signal Ivan Duque’s support, although he is not known as a friend of the peace process, unlike his predecessor Juan Manuel Santos, who had enabled the Havana Accord.

After more than one year of intense communication and coordination with Jack Goldstein, I found myself in Bogotá, together with thirty-six of the world’s most extreme travelers who had flown in from as far as Hong Kong, Singapore, Azerbaijan, Siberian Russia, Finland, and many other countries.

For the opening dinner at the Lancaster House Hotel, we were joined by the heads of the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia, the Agency for Reincorporation & Normalisation, the Tourism Ministry, small FARC producers presenting their coffee and beer brands, and the leaders of FARC, such as their current number one, Rodrigo Londono Echeverri, aka “Timochenko;” their “Foreign Minister” Rodrigo Granda; their Senator, Victoria Sandino; their Director of Communications, Martin Cruz Vega; and one of only two surviving founding members, 79-year-old Miguel Angel Pascuas, aka “Sergeant Pascuas” or “Black Death,” who is said to have killed more than 800 government fighters in the battle for one city.

Seated next to Jack Goldstein’s wonderful girlfriend Sandy, she told me in a touching, emotional way how impressed she was by her boyfriend being able to unite those former warring parties, and now to sit with those famous or rather infamous names in the same room, all hopeful for a better future. Just a while ago, it would have been as unthinkable for her as it was for me to ever meet a FARC member in flesh and blood. They were names as distant as Pluto or Mars.

Well, I think it must have been more terrifying for her as a Latin American than for me from my safe distance in Europe. On the other hand, nowadays, the rehabilitated FARC leaders still have to fear for their safety, not only because of potential spontaneous encounters with revenge-seeking victims but also because of the clandestine killings within their ranks, some probably conducted by right-wing paramilitaries and possibly with secret government endorsement. Therefore, the current FARC leaders each have at least 3 bodyguards, made up of 1 former FARC, 1 police, and 1 private contractor, plus bulletproof SUVs, all paid for by the government (or rather the Colombian taxpayers).

Early next morning, our convoy of bulletproof cars, UN Land Cruisers, and tourist minivans set itself in motion for a slow 14-hour drive to the village of El Oso, in the department of Tolima, where a provisional FARC reconciliation center has been set up by the government.

We were constantly escorted by a dozen heavily armed policemen on the back of police pickups, plus several policemen on motorbikes. In addition, the Military Bataillons 18 and 19 had secured all surrounding areas for us with several hundred soldiers. We had to pre-communicate our blood groups, and there was a military helicopter on standby for us, just in case. After the event, we were told that there had been some clashes only about 20 to 30 kilometers away from us, but it was unclear to me if it was with FARC renegades or other conflicting parties.

At one point, when a damaged car tire had to be repaired, I had the opportunity to speak with a high-ranking police officer of GAULA, the special forces against kidnappings and extortions. Although his team was providing perfect protection in the most professional way, not only for us but also for his former enemies from the FARC side, he indicated to me that privately he still thought that “Marquetalia is the problem!”, meaning he sees no good in FARC, now or in the future, just like the majority of his countrymen (the peace accord was rejected by a small margin in a referendum).

Admittedly, I am pretty sure that because of my upbringing, I also would have become a right-wing person in Colombia, but I completely understand that a rural indigenous Colombian will be more inclined to fight for the left. In any case, after the joint hardship of this adventure, I consider myself a personal friend of FARC leader Martin Cruz Vega, no matter the differences in our curricula vitae. And I have a hunch that this charismatic and hardworking leadership personality will quickly find the road to success as a businessman, now that he has officially left the armed fight for Marxism-Leninism. Abrazo y mucha suerte, Martin! A hug and good luck to you!

In El Oso, our group also met, for the first time, the most famous face of FARC: the Dutch revolutionary Tanja Nijmeijer, who came to Colombia as a 19-year-old language teacher 20-some years ago and then stayed on to fight in the jungle. Tanja comes across as the live Lara Croft, with a captivating charisma that has undoubtedly enabled her to lead whole fighter battalions, sometimes in the wrong direction, with just a flirtatious gaze and a coquettish brush of her hair.

She certainly knows and enjoys her effect on men. What she doesn’t seem to acknowledge is that the world is not driven exclusively by workers and peasants. When my German travel mate Thorsten introduced himself to her as a businessman, she looked at him as if he were an unknown insect, countering with, “So you are a businessman?” in the way I would say, “So you are a voodoo priest?” or, “You are a social justice worker?”

Along similar lines, Tanja described her new hometown Cali as “a sea of highrise buildings entirely built by drug money,” as if there were no legitimate economic activity and property development in this world besides agri-barons or the illicit drug trade. Funnily, Tanja Nijmeijer then announced her resignation from FARC, via international news agencies, on the day after our encounter. There are several manly foreign travelers among us who still argue about who had that final impact on her decision. In any case, from my point of view, I say, “Congratulations, Tanja! A wise decision!” She is definitely the most charismatic female I ever met, with the male contender being Alexander Saldostanov, aka Chirurg, who is the chief of the Russian Night Wolves.

Back to our trip. After a short night in a provisional tent camp in El Oso, we had to swap vehicles because of the terrible onward road. It took us another two hours to reach the village of Villanueva in a convoy of a dozen UAZ jeeps, mostly from Soviet times. Go figure! Yes, the rebel areas somehow have Russian cars; in the coffee areas, there are mostly Willys jeeps from the Korean War, where Colombia fought alongside the US; the government security forces still use a lot of US vehicles; and normal Colombians privately prefer German cars (or Japanese) just like everywhere else—the big conflict explained in one small market distortion.

At the road end in Villanueva, participants had to leave the relative comfort of their 4x4s and choose between horseback, mule, or trekking on foot. The next five hours on the narrow mountain path were grueling. Occasional rain made the rocks slippery and the trail muddy.

My horse seemed to have a death wish and continuously let its head hang over the edge of the 300-meter-high ridge on the valley side. It was a miracle that there were no casualties or missing persons on the last kilometers of our Peace Road to Marquetalia. In all fairness, FARC did the best possible job in such conditions, no doubt aided by their many years of experience in mountain and jungle terrain.

We finally reached Manuel Marulanda’s hut on the top of the Marquetalia plateau in torrential rainfalls. Our tents were not completely dry in the rain, but who wants to complain about a brand new rebel hotel that is not even listed on TripAdvisor yet? The atmosphere around the campfire, listening to anecdotes from Martin Cruz Vega, Tanja Nijmeijer, and other rebel leaders, captured all of us, even those who got lost in the translations from Spanish to English.

The field kitchen was excellent, serving mostly rice and lamb, or chicken stew, prepared over the open fire in huge cauldrons. The muscle aches ensured a quick sleep. Only a few of us used the optional “shower” in the cold mountain stream in the morning. I think one was a brave Finn and the others were Russian.

Just like FARC, our travel group was comprised of almost one-half men and one-half women. The second-most-famous FARC lady, the Afro-Colombian Mulato senator Victoria Sandino, left a lasting impression on me. In a TV interview with private news channel Red+ Noticias, who had accompanied us all the way to Marquetalia, the senadora was asked by reporter Gabriel Romero, “What is the best system for Colombia in the future?” to which she replied, “El Socialismo! It is Socialism, of course!” Then she suddenly put her hand over the reporter’s microphone, asked him to stop filming and cut the sequence, and then she shouted at the top of her voice toward someone in the tent camp: “Hey you! Back off! This is my plastic bag!” What a laugh. All the self-contradictions of the left were packed into one small phrase—into a plastic bag, of all places.

Now this is sustainably conserved on the Red+ YouTube feed and on my Twitter. The otherwise perfectly neutral reporter had left that sequence in the movie, and it was simply too good to be cut.

Yes, we did all make it back home in one piece, although the trip changed some of us forever—not necessarily in a political way, but in a deeply human way of looking at how we interact with perceived opponents. Libertarians, especially, know that the current powers that be try to divide us from our neighbors by calling the objective historical truth a lie or merely one of many opinions, whereas their reality design (manmade climate change, gender ambiguity, white guilt, etc.) has become the official party line, the sacrosanct truth.

This is all a result of highly professional propaganda and agitation. The challenge (and the opportunity) for today’s bona fide freedom fighters is that we live in the times of smartphones and social media, not Kalashnikovs and kidnappings. Fake heroes like Greta become manufactured household names, whereas real heroes are censored, de-monetized and shadowbanned.

Interestingly, and against their founders’ and inventor’s intentions, Facebook, WhatsApp, and emoticons may also have a healing effect on us. Back home in Europe, the four German participants of the Peace Road to Marquetalia delivered a trip report in the member lounge of their cigar club in the city of Munich, with live support from Tanja Nijmeijer coming directly from Colombia via Whatsapp.

The whole audience, including several German princes, businessmen, and other bourgeois elements, saluted the Marxist rebel with thumbs up, smiles, and victory signs. And Tanja answered back with her trademark air kisses. Connecting people instead of kidnapping people—imagine what WhatsApp would have done to the myth of Che Guevara?!

Editor’s Note: International Man is all about helping you make the most of your personal freedom and financial opportunities around the world. We just released a new report called Getting Out of Dodge written by contrarian investing legend Doug Casey. Inside is his action-packed survival guide. Click here to download the PDF now.

Tags: colombia,